Back in 2012, Apple introduced iCloud alongside iOS 5. At the same time, the company announced that developers would have access to iCloud through a number of APIs. Up until now, developers have had three options:

- key-value storage

- document storage

- Core Data integration

These APIs aren’t perfect though. A major shortcoming is their lack of transparency. Core Data integration in particular has led to frustration and confusion among even the most experienced developers. When something went wrong, developers had no idea what or who the culprit was. It could be a problem in their code or in Apple’s.

CloudKit

At WWDC 2014, Apple introduced CloudKit, a brand new framework that directly interacts with Apple’s iCloud servers. The framework is comparable to a number of PaaS (Platform as a Service) solutions, such as Firebase. Like Firebase Apple provides a flexible API and a dashboard that offers developers a peek into the data stored on Apple’s iCloud servers.

What I like most about CloudKit is Apple’s own commitment to the framework. According to the company, iCloud Drive and iCloud Photo Library are built on top of CloudKit. This shows that the CloudKit framework and infrastructure is robust and reliable.

As a developer, this sign of trust and commitment is important. In the past, Apple occasionally released APIs that were plagued by bugs or lacking key features simply because the company wasn’t eating its own dog food. This isn’t true for CloudKit. And that is promising.

Should You Use CloudKit

Key-value storage and document storage have their use and Apple emphasizes that CloudKit doesn’t replace or deprecate existing iCloud APIs. The same is true for Core Data. CloudKit doesn’t offer local storage, for example. This means that an application running on a device without a network connection is pretty much useless if it solely relies on CloudKit.

Apple also emphasizes that error handling is critical when working with CloudKit. If a save operation fails, for example, and the user isn’t notified, then she may not even know that her data wasn’t saved—and lost.

CloudKit is a great solution for storing structured as well as non-structured data in the cloud. If you need a solution to access data on multiple devices, then CloudKit is certainly an option to consider.

During this year’s WWDC, Apple did what few developers had expected or hoped for. It announced a web service for CloudKit. This means that CloudKit can be used on virtually any platform, including Android and Windows Phone.

Apple’s pricing is pretty competitive too. Getting started with CloudKit is free and it remains free for most applications. Again, CloudKit is certainly worth considering if you plan to store data in the cloud.

CloudKit Concepts

Developers struggling with Core Data are often unfamiliar with the building blocks of the framework. If you don’t take the time to learn about and understand the Core Data stack, then you will inevitably run into problems. The same is true for CloudKit.

Before we start working on a sample application that uses CloudKit, I want to spend a few minutes introducing you to a number of key concepts of the CloudKit framework and infrastructure. Let’s start with containers, databases, and sandboxing.

Privacy and Containment

Apple makes it very clear that privacy is an important aspect of CloudKit. The first thing to know is that each application has its own container in iCloud. This concept is very similar to how iOS applications each have their own sandbox. However, it is possible to share a container with other applications as long as those applications are associated with the same developer account. As you can imagine, this opens up a number of interesting possibilities for developers.

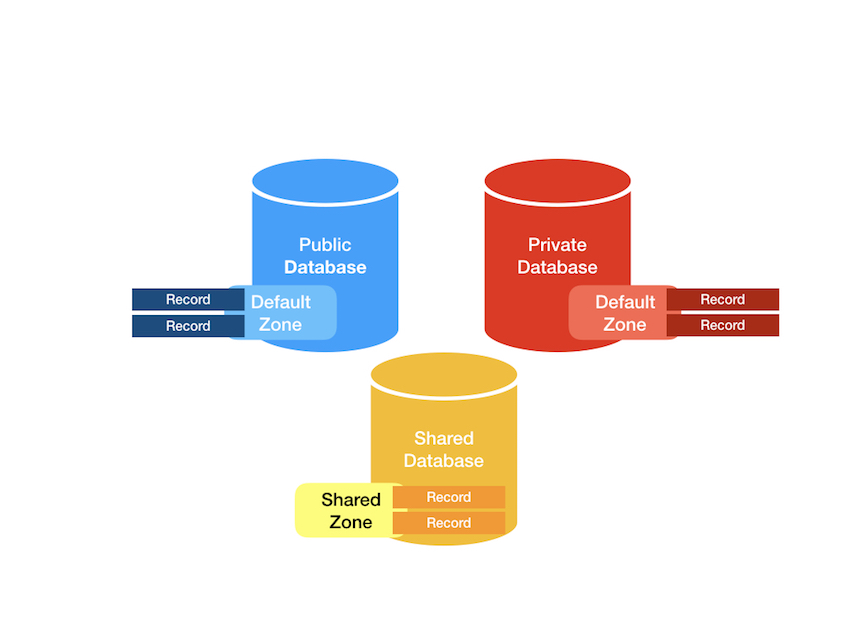

A CloudKit container contains several databases. Each container has one public database that can be used to store data that is accessible to every user of your application. In addition to the public database, a container also contains a private database for each user of your application. The user’s private database is used to store data that is specific to that particular user. Data segregation and encapsulation is a key component of the CloudKit and iCloud infrastructure.

Even though an application’s container can hold many databases, from a developer’s perspective a container holds only two databases, the public database and the private database of the user that is currently signed in to their iCloud account. As of 2017, Apple introduced a third database, shared database, providing apps with the ability to share a subset of records that is shared and on other user’s private database, inviting them to contribute to those exposed records.

I’ll talk more about iCloud accounts a bit later.

Records and Record Zones

The databases of an application’s container store records. This isn’t very different from a traditional database. At first glance, the records stored in a CloudKit database seem to be nothing more than wrappers for a dictionary of key-value pairs. They may look like glorified dictionaries, but that’s only part of the story.

Each record also has a record type and a number of metadata fields. A record’s metadata keeps track of when the record was created, which user created the record, when the record was last updated, and who updated the record.

The CKRecord class represents such a record and it’s a pretty powerful class. The values you can store in a record aren’t limited to property list types. You can store strings, numbers, dates, and blobs of data in a record, but the CKRecord class also treats location data, CLLocation, as a first-class data type.

You can even store arrays of the supported data types in a record. In other words, arrays of strings or numbers are no problem for a CKRecord instance.

Records are organized in record zones. A record zone groups related records. The public and private database each have a default record zone, but it is possible to create custom record zones if needed. Record zones are an advanced topic that we won’t discuss in much detail in this series.

Relationships

Relationships between records are managed by instances of the CKReference class. Let’s look at an example to better understand how exactly relationships work. The application we will create in this series will manage a number of shopping lists. Each list can have zero or more items in it. This means that each item needs to have a reference to the list it belongs to.

It’s important to understand that the item keeps a reference to the list. While it is possible to create an array of CKReference instances for the items of a list, it is more convenient—and recommended—to keep the foreign key with the item, not the list. This is also what Apple recommends.

The way CloudKit manages relationships is fairly basic, but it does provide an option to automatically delete a record’s children when the parent record is deleted. We’ll take a closer look at relationships a bit later in this series.

Assets

I also would like to mention the CKAsset class. While it’s possible to store blobs of data in a record, unstructured data, such as images, audio, and video, should be stored as CKAsset instances. A CKAsset instance is always associated with a record and it corresponds with a file on disk. We won’t be working with the CKAsset class in this series.

Authentication

I’m sure you agree that CloudKit looks quite appealing. There is, however, an important detail that we haven’t discussed yet, authentication. A user authenticates itself through its iCloud account. If a user isn’t signed in to their iCloud account, then they’re unable to write data to iCloud.

While this is true for any of the iCloud APIs, keep in mind that applications that solely rely on CloudKit won’t be very functional in that case. All the user can do is access the data in the public database, if permitted by the developer.

Reading Data

If a user isn’t signed in to their iCloud account, they can still read data from the public database. It goes without saying that the private database is not accessible since iCloud doesn’t know who is using the application.

Reading and Writing

When signed in, the user can read and write to the public and their private database. I already mentioned that Apple takes privacy very seriously. As a result, the records stored in the private database are only accessible by the user. Even you, the developer, cannot see the data the user has stored in its private database. This is the downside of Apple managing your application’s backend, but it’s a definite win for the user.

Shopping List

The application we’re about to build will manage your shopping lists. Each shopping list will have a name and zero or more items. After building the shopping list application, you should feel pretty comfortable using the CloudKit framework in a project of your own.

Prerequisites

For this tutorial, I will be using Xcode 9 and Swift 4. If you are using an older version of Xcode, then keep in mind that you are using a different version of the Swift programming language. This means that you will need to update the project’s source code to satisfy the compiler. The changes are mostly minor, but it’s important to be aware of this.

Because CloudKit is an advanced topic, I am going to assume that you are familiar with both Xcode and the Swift programming language. If you are new to iOS development, then I recommend reading an introductory tutorial first or take one of our courses on Swift development. Derek Jensen has created a course on the Swift programming language as well as a course on iOS development with Swift. Be sure to check those out if you are new to iOS development or the Swift language.

Project Setup

It’s time to start writing some code. Launch Xcode and create a new project based on the Single View Application template.

Enabling iCloud

The next step is enabling iCloud and CloudKit. Select the project in the Project Navigator on the left and select the target for your application from the list of targets. Open the General tab and set Team to the correct team. To avoid any problems in the next step, verify that your developer account has the required permissions to create an App ID.

Enabling CloudKit is as simple as checking the checkbox labeled CloudKit. By default, your application will use the default container for your application. This container is automatically created for you when you enable CloudKit.

If your application needs access to a different container or it needs access to multiple containers, then check the checkbox labeled Specify custom containers and check the containers your application requires access to.

Getting Your Feet Wet

In the next tutorial of this series, we will add the ability to add, edit, and remove shopping lists. To finish this tutorial, however, I’d like to get your feet wet by showing you how to interact with the CloudKit API. All we’re going to do is fetch the record of the currently signed in user.

Open ViewController.swift and add an import statement at the top to import the CloudKit framework.

import UIKit import CloudKit

To fetch the user record, we first need to fetch the record’s identifier. Let’s see how this works. I’ve created a helper method, fetchUserRecordID, to contain the logic for fetching the user’s record identifier. We invoke this method in the view controller’s viewDidLoad method.

override func viewDidLoad() {

super.viewDidLoad()

// Fetch User Record ID

fetchUserRecordID()

}

The implementation of fetchUserRecordID is a bit more interesting than viewDidLoad. We first fetch a reference to the application’s default container by invoking defaultContainer on the CKContainer class. We then call fetchUserRecordIDWithCompletionHandler(_:) on defaultContainer. This method accepts a closure as its only argument.

private func fetchUserRecordID() {

// Fetch Default Container

let defaultContainer = CKContainer.default()

// Fetch User Record

defaultContainer.fetchUserRecordID { (recordID, error) -> Void in

if let responseError = error {

print(responseError)

} else if let userRecordID = recordID {

DispatchQueue.main.sync {

self.fetchUserRecord(recordID: userRecordID)

}

}

}

}

The closure accepts two arguments, an optional CKRecordID instance and an optional NSError instance. If error is nil, we safely unwrap recordID.

It’s important to emphasize that the closure will be called on a background thread. This means that you need to be careful when updating the user interface of your application from within a closure invoked by CloudKit. In fetchUserRecordID, for example, I explicitly call fetchUserRecord(_:) on the main thread.

In fetchUserRecord(_:), we fetch the user record by telling CloudKit which record we’re interested in. Notice that we call fetchRecordWithID(_:completionHandler:) on the privateDatabase object, a property of the defaultContainer object.

The method accepts a CKRecordID instance and a completion handler. The latter accepts an optional CKRecord instance and an NSError instance. If we successfully fetched the user record, we print it to Xcode’s Console.

private func fetchUserRecord(recordID: CKRecordID) {

// Fetch Default Container

let defaultContainer = CKContainer.default()

// Fetch Private Database

let privateDatabase = defaultContainer.privateCloudDatabase

// Fetch User Record

privateDatabase.fetch(withRecordID: recordID) { (record, error) -> Void in

if let responseError = error {

print(responseError)

} else if let userRecord = record {

print(userRecord)

}

}

}

When you run the app in Xcode, you will see in the console something similar to:

This should have given you a taste of the CloudKit framework. It’s modern API is intuitive and easy to use. In the next tutorial, we will dig deeper in the possibilities of the CloudKit API.

You can clone the complete sample project, at Github (tag #introduction)

Conclusion

You should now have a proper understanding of the basics of the CloudKit framework. The remainder of this series will be focused on building the shopping list application. In the next tutorial, we will start by adding the ability to add, edit, and remove shopping lists.

Powered by WPeMatico